INTERVIEW/Story of persecuted Dutch woman in Mao's China showcased at book fair

By Alison Hsiao, Staff Reporter

"Escaped from Hitler, a prisoner of Mao" is the subtitle that Dutch author Carolijn Visser gave to her biography "Selma" and a sad epithet embodying the irony and tragedy of the life of a Dutch woman, Selma Vos, that ended in China's Cultural Revolution.

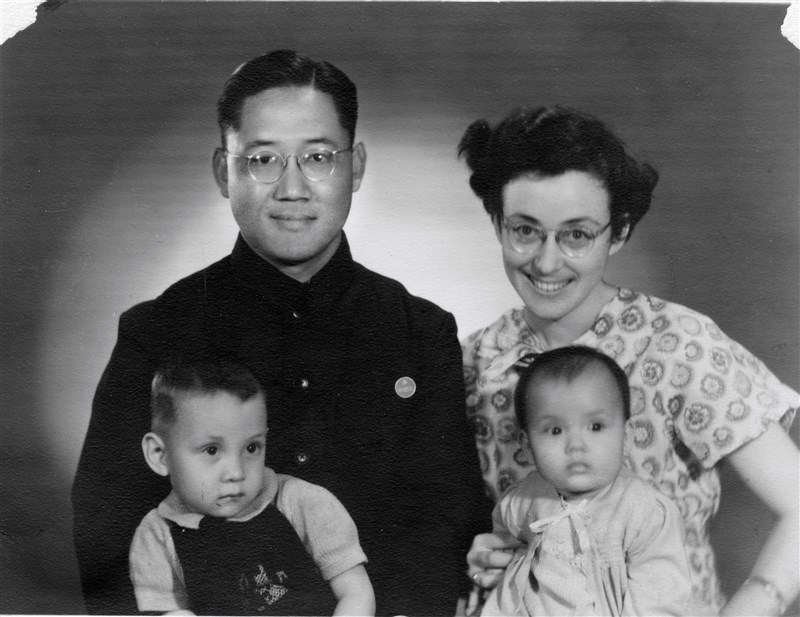

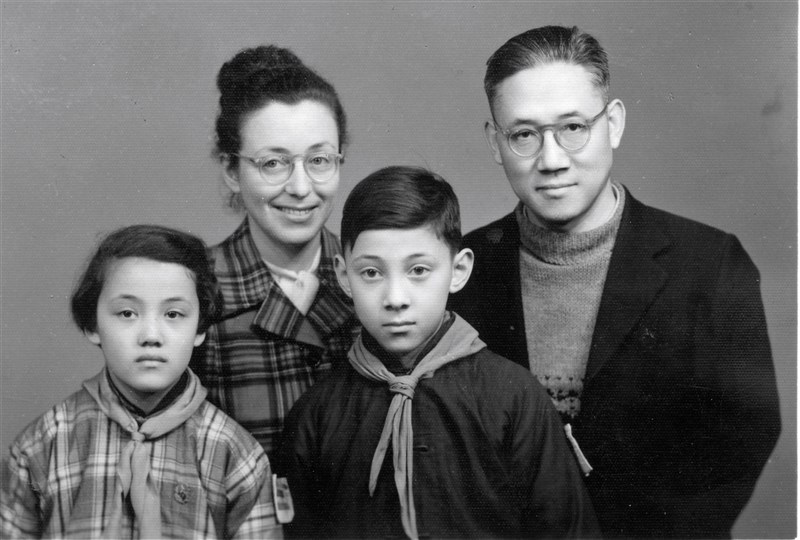

The biography, first published in Dutch in 2017 and recently released in Taiwan after being translated into Chinese, was the idea of Vos' children, Cao Zengyi (曹增義) and Cao Heli (曹何麗), who grew up in Mao Zedong's China before leaving the country in 1979.

It is one of the works being highlighted at this year's International Book Exhibition in Taipei, and Visser will give a talk about the remarkable story of Vos and her family at the six-day fair on Wednesday afternoon.

Vos, born in 1921, survived the Nazis with her father, but her mother and other family members perished in the gas chambers of Sobibor in eastern Poland.

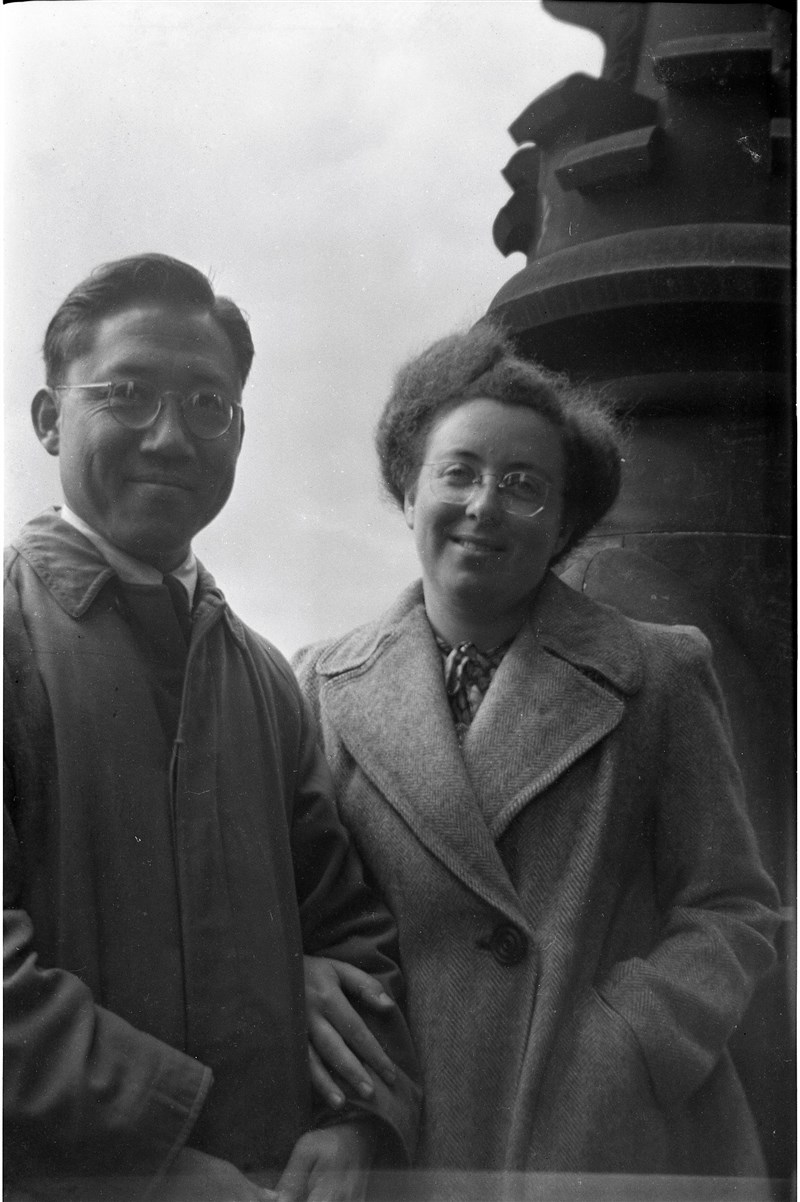

Still in her 20s at the end of World War II, Vos went to school at Cambridge, where she met her future Chinese husband Cao Richang (曹日昌), a psychologist who later was one of the founders of the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences(CAS).

The Cao and Vos went to live in the new China in 1950 with great aspirations, but were later persecuted and died in 1968 during the Cultural Revolution.

Documenting the past

It was a story Vos' two children were keen to tell, and in Visser, who has an interest in communist and post-communist societies and wrote a book about China in the early 1980s after visiting the country, they found an ideal partner.

"Zengyi heard my talk [in the Netherlands] about China in the eighties. He and his sister later attended more of my lecturers, and it was only after they retired did they approach me for the idea of a biography for their mother," said Visser in an interview with CNA.

The children first approached the author in 2008 with the idea, and work began in earnest in 2012.

Nakao Eki Pacidal, the book's Chinese-language translator who spoke with CNA from the Netherlands, explained the children's motivation.

"Tseng-yi and He-li told me that many years after the incident, they found that no one living in their compound [home to families of CAS academics] had tried to document the events, so they assumed the task themselves lest history be forgotten," Nakao said.

Visser said that testing their recall as the book was being written "took emotional tolls on them, that they had to constantly go back [to their closeted memories]."

Though they knew the story, reading the Chinese version was still hard for them, Nakao said, because "Chinese is their native tongue. The impact was imaginably stronger."

The Beijing Life

Vos' two children were the main source of the information found in the book, but Visser also conducted interviews with many people, including the siblings' childhood friends and members of the circle of foreigners who resided in China at the time.

The result is a story that chronicles the family's daily life in calmer times, including trips to Beijing's outskirts and Bedaihe, a resort town only the privileged could visit.

Inevitably, it also delves into the tensions that built as the regime launched one campaign after another, including a "small" one that cost a neighbor's husband's life and a major one that resulted in a nationwide famine.

At the same time, the family was always aware of being under the communist party's watchful eye. Cao Richang, for example, could not converse with a foreign academic without transcribing the conversation in Chinese later.

Vos was even afraid of a spy among her foreign friends. Sidney Rittenberg, a loyal "friend of China," "felt honored to be a spy for the [Chinese] government]," Visser said, citing his memoir.

"He may be traumatized [from his decade-long solitary confinement that started also in 1968] but he made many victims," Visser said.

Another source for the book were the letters Vos wrote to her father Max, with those brought out of China by Selma's foreign friends and sent from a third country providing a more honest picture of what was happening.

One of them, sent in September 1966, reveals that Cao has been labeled as a reactionary academic authority and assigned cleaning work for the previous two months.

It was a coincidence, however, that may have sealed Vos' fate, Visser said.

Until 1964, Dutch law required women marrying foreign citizens to relinquish their passport and switch to their husband's nationality. The law was amended, however, and Selma regained Dutch nationality in 1966 during the five months she spent back home.

Though news of the turmoil caused by the Cultural Revolution caused Vos to hesitate about returning to China, she still went back, but did so as a Chinese national, as an untimely political incident between the Netherlands and the PRC in 1966 meant Vos could not get a Chinese visa for her Dutch passport.

"This is a crucial difference [from other foreign spouses]," Visser said, as the de facto Dutch embassy "could not act on her behalf."

Vos was incarcerated in March 1968 and died the same year, but the actual cause of her death has never been confirmed. According to the book, Zengyi was was told by the Red Guards that she "evaded her punishment," which meant she ended her own life.

'Rehabilitation'

It was not until 2011 in the Institute of Psychology's collection of essays in celebration of the centenary of Cao Richang's birth that Cao and Vos died after facing political persecution.

The essays, provided by Zengyi, also said that Cao was "rehabilitated and had regained his reputation," but Zengyi disagreed because there was no admission of fault on the part of the institute, according to Nakao.

Whatever they could say was "very abstract," Visser said, as seen in the essays' use of language in their commemoration of Cao, such as Cao's"sacrifice for science," and "how the 'struggles' were carried out should be discarded as the fruit of the party's great leadership cannot be wasted."

No monuments have ever been built in China to honor the victims of the Cultural Revolution, but monuments help keep memories alive, Visser said, calling the book "the monument for Selma."

Zengyi and Heli hoped that this monument dedicated to Selma can be seen by more people in Taiwan, Nakao said.

The message they wanted to convey, Nakao said, is "that this is not simply something that happened 60 years ago but something that until today has not been recognized."

"The regime has not changed. What it could do then can be done today. It serves Taiwan no good if this is not well understood as it is currently under the threat of China," Nakao said.

Enditem/ls

![Breaking the wall: Pro Go player Hsu Ching-en eyes top spot in Taiwan]() Breaking the wall: Pro Go player Hsu Ching-en eyes top spot in TaiwanAsk most people in Taiwan to name an active pro Go player and they are more than likely to say Hsu Hao-hung (許皓鋐).03/29/2024 12:01 PM

Breaking the wall: Pro Go player Hsu Ching-en eyes top spot in TaiwanAsk most people in Taiwan to name an active pro Go player and they are more than likely to say Hsu Hao-hung (許皓鋐).03/29/2024 12:01 PM![New Thai envoy pitches for more Taiwanese investment in Thailand]() New Thai envoy pitches for more Taiwanese investment in ThailandThe new Thai representative to Taiwan on Tuesday said his country was open to more Taiwanese investment, particularly in the realms of electronic manufacturing and construction projects.03/13/2024 04:22 PM

New Thai envoy pitches for more Taiwanese investment in ThailandThe new Thai representative to Taiwan on Tuesday said his country was open to more Taiwanese investment, particularly in the realms of electronic manufacturing and construction projects.03/13/2024 04:22 PM![Humbled by nature: Ultrarunner Tommy Chen learns to face himself in solitude]() Humbled by nature: Ultrarunner Tommy Chen learns to face himself in solitudeAfter topping the world in the 4 Deserts Race Series in 2016, Taiwanese ultramarathon runner Tommy Chen (陳彥博) could easily be considered a conqueror of nature.03/01/2024 11:45 AM

Humbled by nature: Ultrarunner Tommy Chen learns to face himself in solitudeAfter topping the world in the 4 Deserts Race Series in 2016, Taiwanese ultramarathon runner Tommy Chen (陳彥博) could easily be considered a conqueror of nature.03/01/2024 11:45 AM

- Society

Thousands of Muslims gather across Taiwan for Eid al-Fitr prayers

04/10/2024 05:13 PM - Politics

New Cabinet to respond to domestic, global challenges: Lai

04/10/2024 04:55 PM - Society

Electronic pet ID card launched by agriculture ministry

04/10/2024 04:51 PM - Business

U.S. dollar closes lower on Taipei forex market

04/10/2024 04:11 PM - Business

TSMC reports highest sales for Q1

04/10/2024 03:52 PM